- For EV Drivers

- For Business

- Incentives

- Alberta incentives

- British Columbia incentives

- Manitoba incentives

- New Brunswick incentives

- Newfoundland and Labrador incentives

- Northwest Territories incentives

- Nova Scotia incentives

- Nunavut incentives

- Ontario incentives

- Prince Edward Island incentives

- Quebec incentives

- Saskatchewan incentives

- Yukon incentives

- Products

- Insights

- Company

- Shop now

There’s no place like home (to charge your EV)

Is lack of access to home charging slowing EV adoption?

By Cory Bullis, Senior Public Affairs Manager at FLO

“There’s no place like home,” Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz sagely told us. This mantra also applies to charging your EV – FLO’s data from over a decade of EV charging shows that if drivers can charge at home or overnight, they usually will (often between 70-90% of their total charging!). But not all potential EV drivers can easily or affordably install charging at home. So how do they charge?

Please join me for a walk down the yellow brick road as we investigate who these garage, driveway or parking spots orphans are – and why they matter.

Home charging unlocks convenience and cost savings

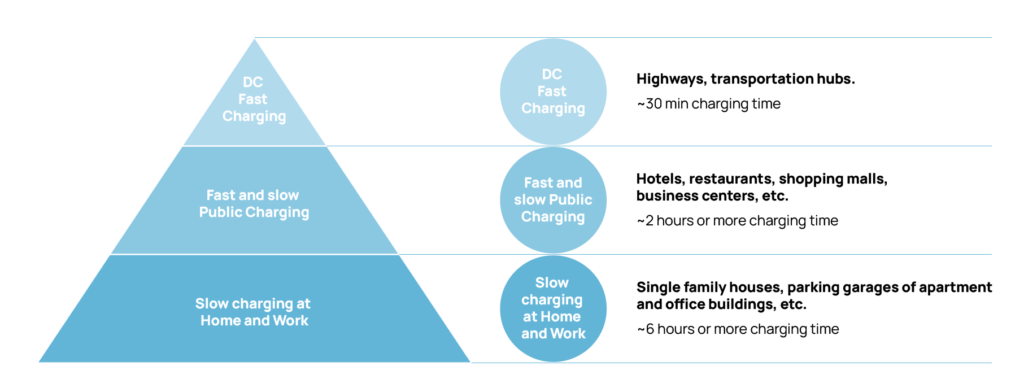

Let’s first consider why being able to charge at night, which is often called “home” charging is so critical to EV adoption. Maslow didn’t create an EV Charging Pyramid of Needs, but if he did, it might look something like the order of chargers needed to support consumer adoption of EVs, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The ideal EV charging “Pyramid of Needs”

All charging types are important, but level 2 stations at home, work, or school are preferred by those with access to them. And it’s easy to understand why. It’s not a perfect analogue, but think of the places you most frequently charge your cell phone. It’s typically at night, while you’re sleeping or at work, if you can find somewhere to plug in conveniently.

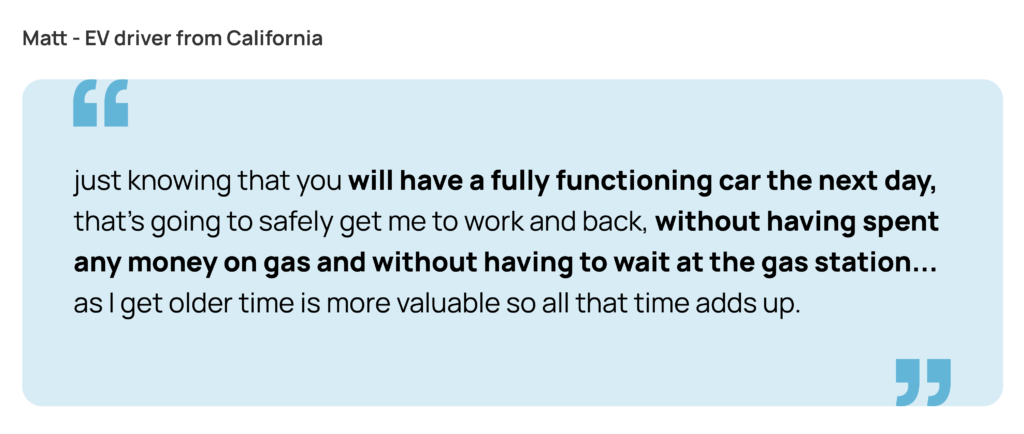

The feedback we gather from our consumer surveys highlights how convenient home charging really is, just like this one:

The case for level 2 charging at home is strong:

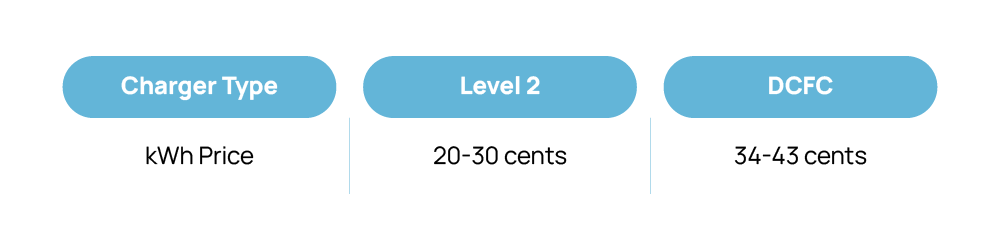

- It’s convenient, typically cheaper to buy and install, and cheaper to operate than public chargers – especially fast chargers (as shown in Figure 2).

- It’s usually less impactful on the grid (especially if it’s networked and part of a demand response program or utility time-of-use rate)1.

- Drivers can easily “set it and forget it” when they come home at night until they leave for work in the morning.

- Drivers also benefit from having a full charge every day, saving them time from having to track down and use public chargers.

Figure 2: Examples of differences in kWh pricing*

Note: DCFC charging session rates are approximately 50 to 100% more than Level 2 charging sessions!

*Price ranges provided as a non-exhaustive sample based on scan of several major networks’ publicly posted charging costs conducted on September 19, 2022. This is not a comprehensive pricing estimate or an offer for charging services to the public on the FLO or any other network.

This convenience becomes an important tool to accelerating EV adoption2, helping to reduce barriers to EV purchases3. Data on charging trends support these findings by showcasing consumer preference for home charging: anywhere from 80 to 90% of drivers charge at home if they can 4,5,6.

And these trends show no sign of changing drastically through 2030. There are several projections for home charger deployment: 7.5 million level 2 ports in the U.S. (representing 78% of total needed chargers)7, 1.1 million level 2 ports in Québec (representing 90% of charging needs)8, and 1.5 million charging ports in Oregon (representing 60% of drivers’ charging needs)9.

The data show that home charging isn’t going anywhere any time soon; and given the benefits, expanding access to home charging and making it work well for the grid will remain important for EV adoption and ensuring drivers get the most from their EVs.

But what about “garage-orphans” who can’t charge at home?

It’s easy to get excited about residential charging, but we must remember that while many households have a garage, or a suitable dedicated driveway or parking spot, lots don’t. Just think of people living in neighborhoods with street parking only, or those living in multi-family homes (MFHs) where installing dedicated charging is impractical or comes with a massive bill.

Remember the projections above, showing that major cities in North America will need millions of level 2 chargers by 2030? Well, these numbers also include the needs of MFH residents who, for one reason or another, often don’t have access to home charging.

For policymakers, providing alternatives to at home charging isn’t a “nice to have”, it’s essential to equitable EV adoption.

What are the roadblocks to EV charging in multi-family homes?

Approximately 41% of Americans in the top 100 metropolitan areas live in MFHs10; in California and Oregon, it’s 31%11 and 25%12 respectively. The most densely populated cities in Canada show similar if not higher numbers – 40% of Toronto and Vancouver’s housing stock comprised of MFHs13.

We can’t ignore the fact that MFHs make up a significant part of our urban building stock.

While some MFHs are designed to accommodate EV charging, or can be easily retrofitted, many have special barriers not faced with typical detached single-family houses. They can include:

- Insufficient access to power

- Crucial infrastructure upgrades being too costly

- Building owners or property managers not being properly incentivized to install chargers

- Renters lacking access to dedicated parking

- Property governance rules making it difficult to install stations in common areas

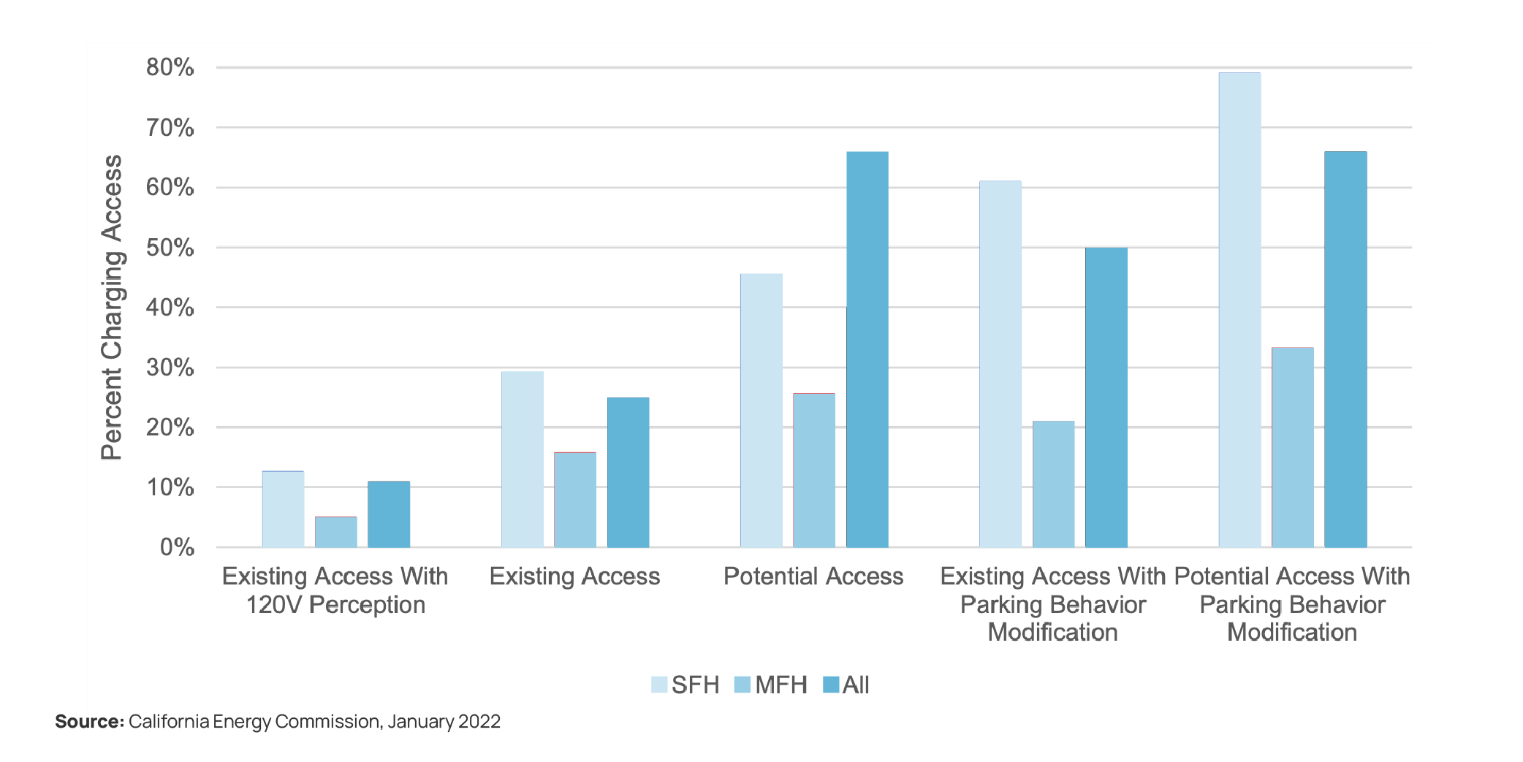

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) found that in a national 100% light-duty EV adoption scenario, 40% of drivers without access to home charging live in MFHs14. Renters at low- and mid-capacity apartment complexes have the lowest charging access (10% and 8%), as opposed to 35% of residents renting detached single-family homes and 58% of residents who own detached single-family homes. That is a stark contrast. California modeled a similar study after NREL’s and found access to charging still does not exceed 33%15 in the state, shown in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Potential EV charging home access at Multi-Family Housing

Their study came to additional concerning and very important conclusions: lower-income residents generally have less access to home charging, and residents who identify as Black, African American, Hispanic, or Latino generally have lower access to home charging than other races16.

Bleak data such as these point to a serious equity problem. How are we going to mitigate disparities in residents’ access to home charging? How can policymakers support EV adoption for people who can’t charge in detached houses?

One answer to these questions is curbside charging, or what we like to call “home-adjacent” level 2 charging, which does wonders for a more equitable transition to EVs. This charging solution meets people where they live, work or study, which is especially helpful for garage-orphans. The next question is: how can we make it happen? That’s a story for next time!

Sources:

- Networked chargers, if it is implemented via software, can specify when to charge, how long to charge, and even set limits on the power level of the charge. These are all important features for reducing load on the grid at peak hours and shifting demand to non-peak hours. And furthermore, due to the typical schedule of home charging (at night after work until early morning the next day), utilities can more easily plan their infrastructure to handle the periods of this expected load, whereas public charging can be more unpredictable.

- Oregon Department of Transportation. Transportation Electrification Infrastructure Needs Assessment. June 28, 2021. Page 20.

- City of Richmond & BC Hydro. Residential Electric Vehicle Charging: A Guide for Local Governments. 2020. Page 9.

- Electric Power Research Institute. Electric Vehicle Driving, Charging, and Load Shape Analysis. 2018. Page v.

- J.D. Power. Level Up: Electric Vehicle Ownerships with Permanently Installed Level 2 Chargers Reap Benefit from their Investment. February 3, 2021. Accessed July 2, 2022. < 2021 U.S. Electric Vehicle Experience (EVX) Home Charging Study | J.D. Power (jdpower.com)>

- Oregon Department of Transportation. Transportation Electrification Infrastructure Needs Assessment. June 28, 2021. Page 10

- Cooper, Adam & Schefter, Kellen. Electric Vehicle Sales Forecast and the Charging Infrastructure Required Through 2030. Institute for Electric Innovation and Edison Electric Institute. November 2018. Page 3.

- Bernard, Marie Rajon & Hall, Dale. Assessing charging infrastructure needs in Québec. The International Council on Clean Transportation. February 2022. Page 21.

- Oregon Department of Transportation. Transportation Electrification Infrastructure Needs Assessment. June 28, 2021. Page 10.

- Schroeder, John et al. EV Charging for All: How Electrifying Raid-hailing Can Spur Investment in a More Equitable EV Charging Network. RMI. 2021. Page 14.

- California Department of Housing & Community Development. California’s Housing Future: Challenges & Opportunities. February 2018. Page 15.

- Oregon Department of Transportation. Transportation Electrification Infrastructure Needs Assessment. June 28, 2021. Page 10.

- Statistics Canada. Census in Brief: Dwellings in Canada. May 2017. Accessed July 2021. < Census in Brief: Dwellings in Canada, Census year 2016 (statcan.gc.ca)>

- Ge, Yangbo et al. There’s No Place Like Home: Residential Parking, Electrical Access, and Implications for the Future of Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. October 2021. Page vi.

- Alexander, Matt. Home Charging Access in California. California Energy Commission. January 2022. Page 18.

- Alexander, Matt. Home Charging Access in California. California Energy Commission. January 2022. Page 34.